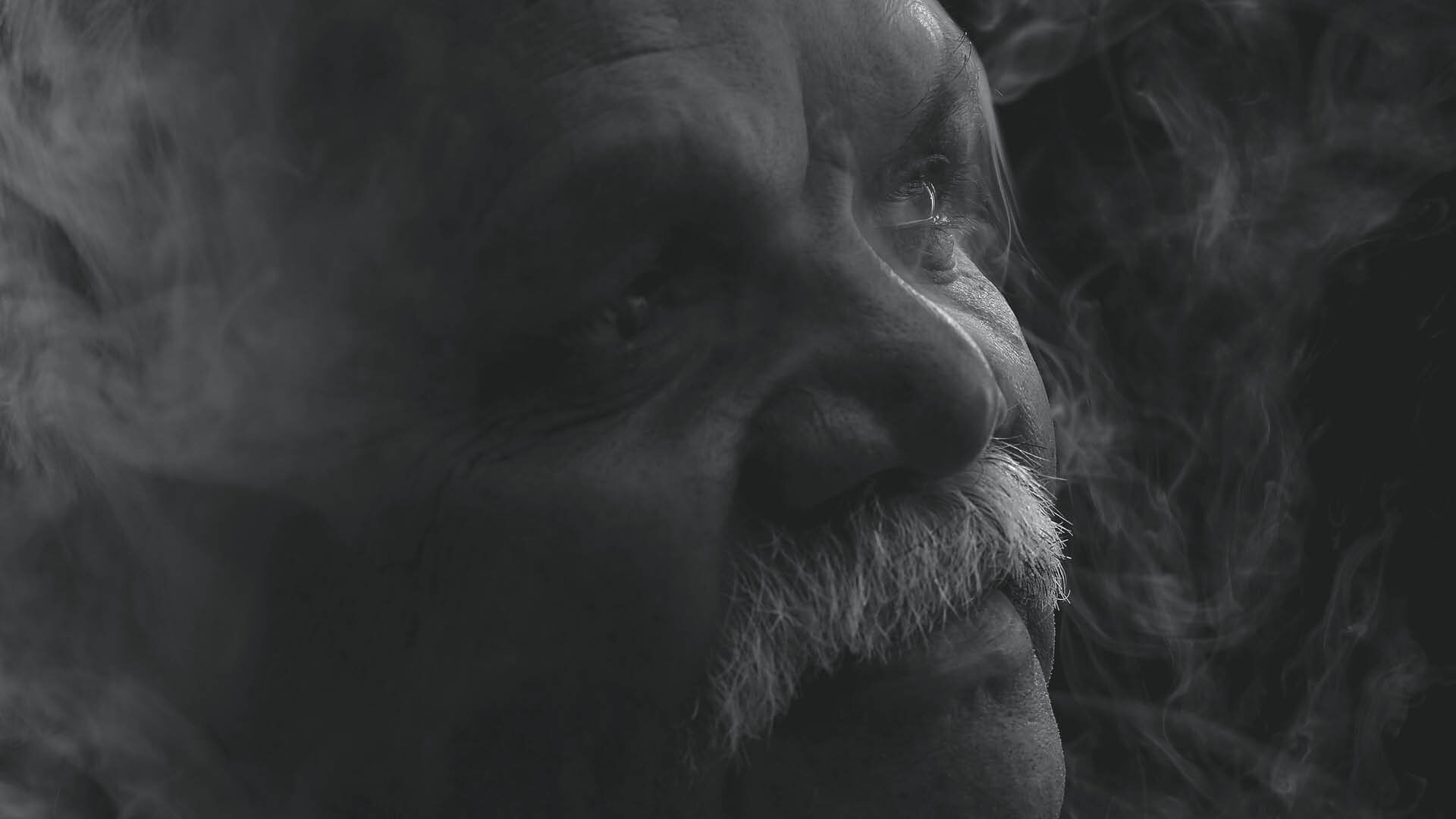

Declared medically blind by Fred Hollows in 1990, second-time president of the Rotary Club of Armidale AM, Aboriginal Elder Steve Widders, is championing Rotary’s diversity, equity and inclusion policy.

By Amy Fallon

Steve Widders first became familiar with Rotary when he was selected for a Rotary Youth Leadership Award (RYLA) as a teenager in regional Australia.

Decades later, he became one of the first Indigenous club presidents and is at the forefront of Rotary’s commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion.

“When I first became involved, Rotary was very white, and although I’ve never been discriminated against, I thought that the only way for something to change is to be part of that change yourself,” says the president of the Rotary Club of Armidale AM, NSW.

The proud Kamilaroi and Anaiwan man, 65, grew up in Armidale with 12 siblings during an exciting time, when activism around Indigenous rights was emerging.

Steve attended what was then one of biggest schools in NSW, where positions as a school representative council member and house captain led to his RYLA nomination.

Later, while completing a teaching degree, he saw an invitation to join Rotaract.

“I wanted to learn a bit more about leadership and being active in your community so thought it was a good start,” says Steve.

He was the only Indigenous person in the group of about 15 at the time.

In 1987, at the age of about 31, he became the first Aboriginal person from his district to travel to India on a “life changing” Rotary-sponsored Group Study Exchange (GSE).

“One of the Rotarians on the selection panel said, ‘You meet all the criteria: young, professional, can articulate yourself well and interested in going overseas – you’re an ‘Aboriginal to boot!’

“I think they realised that including an Aboriginal person might be good for them, too,” Steve recalls.

The former community programs officer with the NSW Department of Community Services (DOCS) found those in his host country accepting, warm and understanding.

“A lot of people there related to me with no problems at all.”

“When I say losing my sight gave me vision, it gave me vision for the future. I saw everything from a different perspective, literally a different perspective. There is a lot of ignorance out there from other people who think because you have a disability you haven’t got ability. Don’t put that ‘dis’ in front of my ‘ability’.”

Steve paved the way for five more Indigenous people from his district to participate in the initiative.

In 1994, he was selected for a Rotary-sponsored Ambassadorial Scholarship to the University of Alaska, US. He spent two semesters in the middle of winter undertaking a comparative study between Australian Aboriginal communities and Alaska’s Inuit people, specifically exploring the impact of colonisation and displacement.

But at age 35, Steve’s life was thrown into upheaval, when the father-of-four was suddenly declared medically blind by Professor Fred Hollows.

“It sent me into depression and almost tore the family apart. I lost my independence and mobility, my role as a father and husband was all challenged.

“But I realised I had an obligation and a responsibility to my family, and decided it was up to me to meet the challenges of losing my sight and its consequences. When I say losing my sight gave me vision, it gave me vision for the future. I saw everything from a different perspective, literally a different perspective.

“There is a lot of ignorance out there from other people who think because you have a disability you haven’t got ability. Don’t put that ‘dis’ in front of my ‘ability’.”

Determined to focus on positivity at this time, Steve became a mentor for an Indigenous youth leadership program and, as part of leadership development, in 2010 embarked on a trek of the 96km Kokoda Track in Papua New Guinea. When asthma prevented him from completing the trail, he went back the following year to tick it off the list.

Then, in 2012 he decided to ride a tandem bike from Brisbane to Sydney with health advocate Dr Mick Adams to raise awareness about men’s health initiatives and healthy communities.

“I wanted to get the message across to men to look after their health,” Steve says.

“Healthy men mean healthy families and healthy families mean healthy communities. It was my way, as an Indigenous man, to raise awareness about men’s health.”

Steve joined the Rotary Club of Armidale AM in 2004, and has been a continuing board member for The Rotary Foundation and community service since 2007.

He first served as the club’s president in 2013-14 and is now undertaking a second stint in the role for 2021-22.

The club was charted in 1991, meaning his term as president coincides with its 30th anniversary.

“When I was inducted as president the first time, I said that I’m all about inclusion and diversity and we have a very diverse community in Armidale, with about 80 different nationalities,” Steve says.

“And while this year’s Rotary International theme is Serve to Change [Lives], I believe as Rotarians we need to do things differently, so we could, within our clubs, be a little innovative and Change to Serve.”

Steve is encouraging his club to build a botanical garden, which will reflect and honour not only our original inhabitants but our diverse multiculturalism.

He is also keen to initiate inter-district study exchange groups within Australia and, in the absence of international travel, advance Rotary’s Youth Exchange program to other districts within our zone.

“I think if COVID has taught us anything, it is to appreciate our own country and how much it has to offer. I really think there is great value in embracing this opportunity.”

He also wants Rotary to expand to include younger people, and those beyond the business world.

“Rotary is in a good position to get a message across and break down a lot of barriers. We need to embrace other minority groups, particularly those with disabilities. Go outside the square is what I’m saying.”