The Indigenous Health Scholarship program is a collaborative project between Australian Rotary Health, participating Rotary clubs, and the State and Commonwealth Governments. The yearly scholarships are awarded to Indigenous tertiary students as a way to address the barriers of tertiary study and qualification in Australian Indigenous populations. Each student enrolled in the program is provided with a $5,000 scholarship.

The program has supported hundreds of students in achieving successful careers within the health industry. Here is just one example of the many outstanding success stories.

Community calling

By Jolyon Attwooll

NewsGP

At the age of 37, Corey Dalton appeared to have it all.

He and his wife Michelle had three beautiful young children. He had a successful career as a police detective behind him.

And from the Perth office tower block where he was now working as a human resources manager, he could look out over the Swan River and enjoy panoramic views of the city.

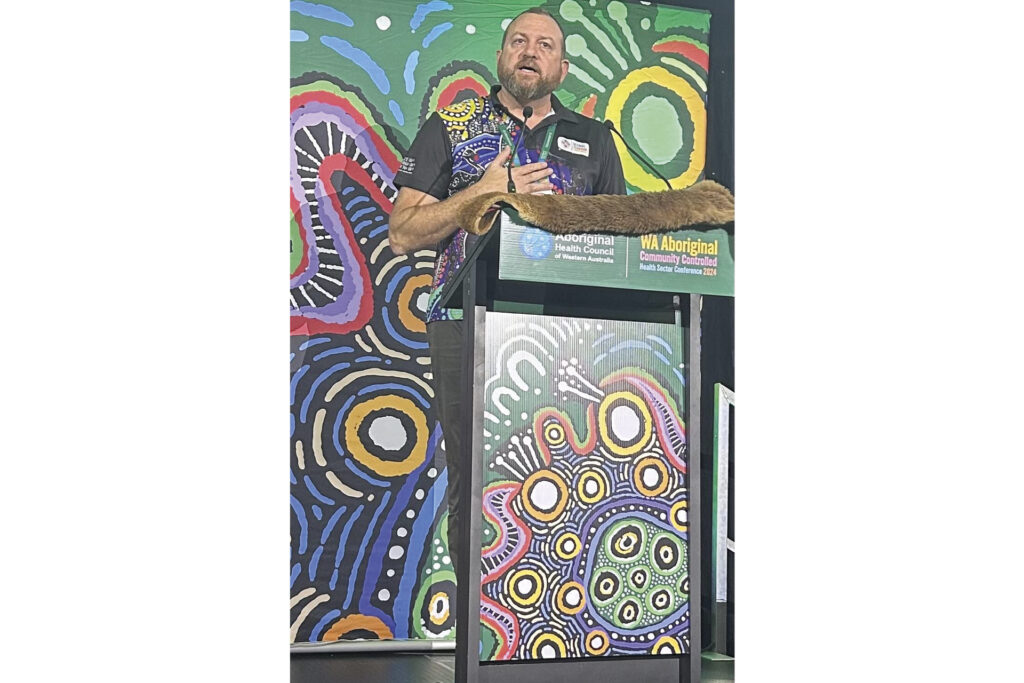

PICTURED: Dr Corey Dalton shared his inspirational journey from adversity to success at the AHCWA (Aboriginal Health Council of Western Australia) Conference in April.

The world seemed at his feet in every sense.

But there was something nagging at his core, a sense of something unfulfilled that he just could not shake.

An Arrernte man, whose grandmother had been taken from her ancestral lands in Central Australia, and whose father had been forcibly placed in a notorious mission school, Corey had been advising a mining company on its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce.

It was a role that took him to meet Professor David Paul, the Associate Dean of Aboriginal Health at Fremantle University – and it is Professor Paul that he credits with re-awakening a dream he thought had slipped beyond his grasp.

“I always had in the back of mind that I loved medical science,” Dr Dalton says.

Having gained a place to study at university straight from high school, he found the experience an unhappy one and abandoned his studies early.

“I failed that whole year,” he recalls. “I failed every unit and both semesters.

“In retrospect, when I look at it, I suppose the culture of university was just not natural to me.

“This is in 1995, there was no cultural connection. I was a fish out of water, I didn’t feel like I belonged there.”

Many years later, it was Professor Paul who suggested he give it another go.

PICTURED: RACGP President Dr Nicole Higgins presents Dr Dalton with his GP in Training of the Year award.

Despite the panoramic views, the mortgage, the young children, including a daughter of six months, and the naysayers, Corey – and, crucially, Michelle – agreed.

He remembers the exact turning point, after the professor asked him to bring in his CV.

“So I took it in and I met with him in his room on campus, and he had a look and he said, ‘Corey, you can do this’.

“And I didn’t believe I could.”

After a crash course to re-surface long-forgotten chemistry and physics, Corey gained a place to study medicine in 2016 at the University of Notre Dame at the age of 38.

“I had a few non-believers out there,” he says. “[Asking] ‘What are you doing? You’ve got a great job’.

“But the drive in me was so strong, that I knew that if I didn’t do it then I would never do it.”

It was obvious he had not chosen an easy road. The study, particularly in the first year, was tough, and not everyone was encouraging.

“I very much had that impostor syndrome of ‘I don’t belong here, I don’t believe I can do this’,” Dr Dalton recalls.

“Even in medical school, it’s a very competitive bunch, and sadly because I went in through the Indigenous pathway, I had people saying, ‘you didn’t get in like everyone else… can you really do this?’

“But I did, I did well, and loved every minute of it.”

From the second year, Corey found his feet, and with the staunch support of his family, he continued to navigate his studies.

He describes how at one point every room in the family home was plastered with medical details, each with a different theme. The family room was dedicated to cardiology, the living room became a shrine to psychiatry, while every wall and window in the dining room was covered in Post-it notes about respiratory and infectious disease.

It was a process with unexpected results at times – Corey describes how his son, James, a talented basketballer, surprised a GP with a precise clinical description of an injury (“second digit, distal phalanx”).

And then the studies were done, the Post-it notes were barbecued – and Corey had become Dr Dalton.

“It’s past what I could ever expect it to be,” he said.

“I never thought of being a GP. I actually went into medicine and wanted to do psychiatry because I’ve got an interest in mental health.

“It was only through med school, when I did a GP placement as a student in my third year for two weeks.

“And in the first week, I changed, I said, ‘That’s it, I’m going to be a GP, this is what I want to do’ and then purposefully directed my studies that way.”

PICTURED: Dr Dalton travelled with his son James to receive his award in October. (Photo: Stuart Winthrope)

Having stayed connected to Arrernte culture, spending weeks at a time with relatives in Central Australia during his school holidays, Dr Dalton felt drawn to work with Aboriginal communities.

It was a feeling that had stirred while he was stationed as a police officer in a town called Pingelly in the wheatbelt of Western Australia.

“That’s where I felt my calling came to give back to my community in the Indigenous sense,” Dr Dalton says. “I was getting knocks on our door at three o’clock in the morning, because people didn’t feel comfortable going to the police station to talk to anyone else.

“They knew I was an Aboriginal man, and that I understood the culture, and understood where they were coming from in certain things.

“So I would help them deal with that and worked closely with the families while I was stationed there, which was really rewarding.”

Now he is fulfilling that calling as a GP-in-training at the Derbarl Yerrigan Aboriginal Medical Service in East Perth.

Dr Dalton talks passionately about the work, and its challenges, mentioning a young patient on the renal transplant waiting list due to chronic disease and diabetes.

“It’s advocating for young people like this … if we don’t, I can’t see them living past 30,” he says.

“Our elders that have lived through all the turmoil of racism in Australia, they come through and bring their kids … and their grannies, because they have that trust with us as their doctor.

“That’s probably one of the biggest joys I get out of working there.

“We’re working at the grassroots level to try and give them the healthcare they need.”

Dr Dalton works with specialists, including with a paediatrician, and has helped introduce an ENT specialist clinic in the suburb of Mirrabooka, as well as going on prison visits and hosting medical students.

It was exactly that sort of commitment and drive that brought him the national GP in Training of the Year award this year, an accolade he can still scarcely believe he won.

“I never thought I’d be standing here, let alone be a doctor,” he says on receiving the award.

Next year, he will navigate the final hurdle towards Fellowship and will be 46 when he expects to graduate.

He still expresses his gratitude to his family, particularly his ‘very supportive and understanding wife’ – and for the decisive influence of Professor Paul.

“I owe him a lot,” Dr Dalton says. “In my personal and professional career, he doesn’t realise how much he’s done for me.

“In my heart, in my mind, it comes back to him every single time.

“What I see him doing for Aboriginal people out there to further their education and careers is where I take a leaf out of his book.

“If I can do a percentage of what he’s done for people, I’ll be happy.”

Corey Dalton received ARH Indigenous Health Scholarship for 2017-19. He was sponsored by Lindsay Couzens Aboriginal Education Trust.

MAIN PICTURE: Dr Corey Dalton was named GP in Training of the Year at the 2023 RACGP awards. (Photo: Jacob Pinskier)